18th Century Embroiderers

Looking at portraits and illustrations of 18th century embroiderers can help us understand how garments and accessories were embroidered, and the the tools and techniques used by embroiderers.

We can also examine unfinished embroideries, some of which have been preserved along with the materials that should have been used to complete the work. Connecticut Historical Society 1935.10.1 (c. 1750-1755), for example, is an unfinished embroidery of the Pitkin family coat of arms “worked in shades of red, pink, brown, and green silk and silver metallic thread on a black satin-woven silk ground, using a shaded satin stitch and other stitches … The unfinished portions of the coat of arms are outlined in white paint.” The embroidery remains attached to the slate frame on which it was worked: “The ground is whip-stitched to plain-woven linen backing and nailed to a wooden embroidery frame. The wooden frame is constructed of four rails, each with a lap joint at the end that is secured with a removable wooden pin.” Some of the skeins of silk accompany the work: “81 skeins of silk thread wrapped in paper, some with printed text; 3 round bundles of silk floss, in white, pink and salmon; 3 twisted bundles, or sticks, of silk floss in cream, gold and bronze; 6 lengths of metallic thread wrapped around a wooden reel or paper; 3 nails; several needles left in the skeins. The unused skeins of silk were originally wrapped in plain gray paper and tied together in groups by color. The used skeins were rewrapped in blank, hand-written or printed paper.”

MoMu Fashion Museum Antwerp T12/1012/E32 (c. 1780-1800) consists of an embroidery kit and an unfinished embroidered waistcoat front. The cardboard box itself is covered with wallpaper on the outside and lined with domino paper on the inside. The internal compartments contain embroidery threads, chenille, and ribbon.

While many young women learned embroidery as part of a complete education, others apprenticed to become professional embroiderers. Read more about the skills required for this sort of career in The London Tradesman (1747) and The Parent’s and Guardian’s Directory (1761).

Additional Resources

Patterns of Perfection: embroidery patterns published in magazines, 1770-1819

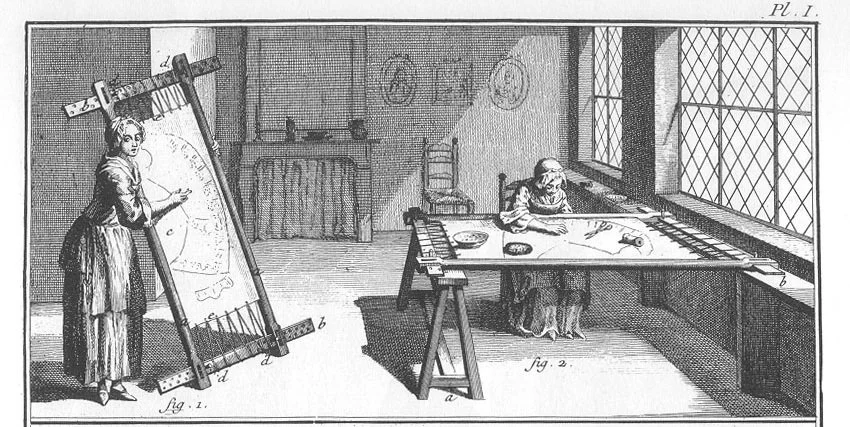

From the Encyclopédie ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers (1765):

THE vignette represents an embroidery workshop.

Fig. 1. The frame holds very taut. The frame is composed of two beams (a a), and two slats (b b); on c we see the fabric on which the design of a jacket has been traced to be embroidered.

Before stretching the fabric on the frame, it must be edged all around with a well-sewn strip of canvas. It is this strip that is then sewn to the edges of the beams, and through which the strings that go around the slats pass, so as to not ruin the fabric.

2. Represents a woman busy embroidering; her frame is placed horizontally on a trestle (a) and on a wooden platband (b) extending across the entire breadth of the windows, to accommodate as many frames as would be necessary.

The worker's right hand is placed on the fabric to receive the needle that the left hand, which is underneath, will pass to it.

When the worker cannot reach the part she wants to embroider, she rolls her fabric onto one of the beams.

(See the original text at the ARTFL Encyclopédie.)

This waistcoat front from the 1760s (Met 1981.14.6a, b) has been embroidered — likely by a similar workshop — but not fully cut out of the fabric beyond cutting out and basting on the pocket-flap. Many uncut embroidered waistcoat panels also include small embroidered circles, which would have been the fabric covers for buttons.

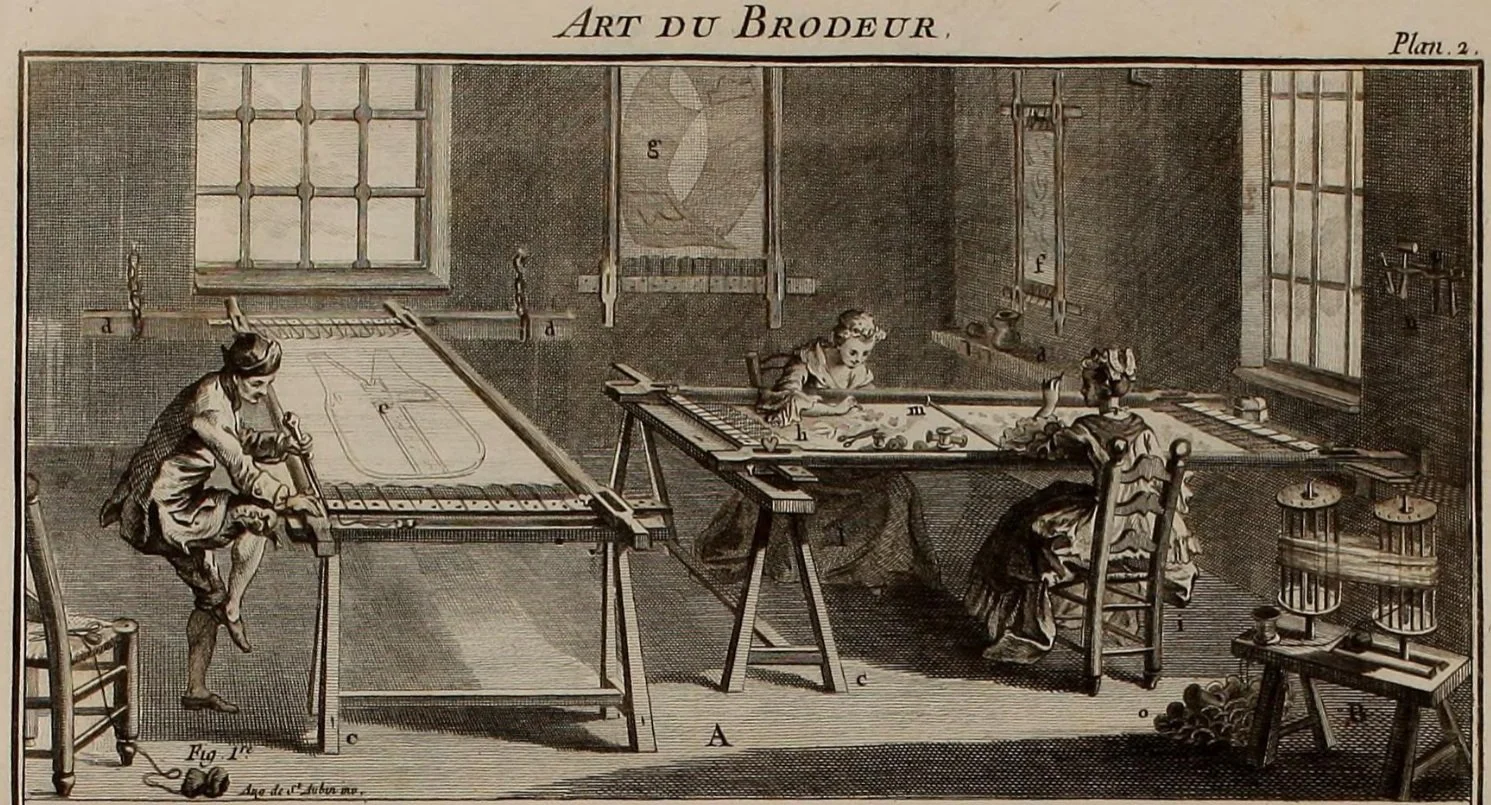

Another embroidery workshop, as depicted in L’art du brodeur (1770) — in which Charles Germain de Saint-Aubin, an embroidery designer during the reign of Louis XIV, explains embroiderers’ tools and how they were used, and discusses several of the styles of embroidery produced in late 18th century France.

In her 1790 portrait, Anna Dibble Tucker holds a piece of partially embroidered black silk laced onto a slate frame; she’s working on outlining the design for her embroidery in white paint.

An unfinished c. 1750 embroidery by a member of the Pitkin family shows a similar white outline on the unembroidered black silk. While the lacing and pegs are gone, the embroidery is still attached to a slate frame.

Connecticut Museum of Culture and History 1935.10.1

The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. Museum Purchase.

Both of these unfinished embroideries began with a design drawn onto the linen canvas. The inked outlines are still visible in the unembroidered spaces.

These canvaswork panels both reflect a typical style produced by girls learning embroidery in New England in the 18th century: a few humans and animals arranged on a rolling pasture, with abstract trees on the side and a house on the far horizon.

It’s possible that Lucy Palmer drew her own design, while Ann Gardner had the “reclining shepherdess” design (a subject frequently stitched by Boston-area schoolgirls of the time) inked by an instructor or a draftsman employed by her school.

(See also Women’s Work: Embroidery in Colonial Boston, With Needle and Brush: Schoolgirl Embroidery from the Connecticut River Valley, 1740-1840, and Connecticut Needlework: Women, Art, and Family, 1740-1840.)

18th century depictions of embroiderers

(Images of embroiderers working on tambour have been moved to the notebook page on tambour embroidery.)

Embroidery lessons by E. Porzelius, 1689

Het Menselyk Bedryf: The Embroiderer by Jan & Caspar Luyken, 1694

Woman in an interior, c. 1700

The Montagu family and an unknown attendant by William Hogarth, c. 1730-1735

The Embroiderer by Jean-Baptiste-Simeon Chardin, 1735-1736

A young embroiderer of Constantinople by Jean-Étienne Liotard, 1738

The Embroiderer by Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin, c. 1740; also here

The Hard-Working Mother by Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin, 1740

Laboratorio di ricamo by Pietro Longhi

Madame Antoine Crozat by Jacques-André-Joseph Aved, 1741

The Marquise de Castellane with her embroidery by Jacques-André-Joseph Aved, c. 1743-1766; see also The mystery of Jacques Aved and a French revolutionary’s grandmother

A portrait of the Vigor family: Jane Vigor, Joseph Vigor, Ann Vigor, William Vigor and probably John Penn by Joseph Highmore, 1744

Embroidery frame, mid-18th century

Portraits of women by Louis Carrogis Carmontelle, including:

Portrait of a lady, 1759

Madame la duchesse de La Vallière, 1760

Madame la comtesse de Damas

Lady Elizabeth Harcourt by Paul Sandby, c. 1759-1760

Horace Walpole’s Nieces: The Honorable Laura Keppel and Charlotte, Lady Huntingtower by Allan Ramsay, 1765

Marquise de Caumont La Force by François Hubert Drouais, 1767

Herzogin Maria Charlotte Amalie von Sachsen-Gotha und Altenburg by Johann Georg Ziesenis, 1768

The young embroiderer at the birdcage by Jacobus Buys

Penelope, 1780

The young embroiderer by Jean-Étienne Liotard

Young woman embroidering by Jean-Etienne Liotard

Maria Amalia of Habsburg Lorraine by Jean-Etienne Liotard

An embroidery workshop by Augustin de Saint-Aubin

Anna (Dibble) Tucker by Ralph Earl, 1790 (displayed at the Met as Sarah Tucker; now at DIA)

Portrait of the artist’s wife and son by Henri-Pierre Danloux, 1790

Lady Jane Mathew and her daughters, c. 1790

Genius & Industry, 1797

An elegant lady in a garden, embroidering by Jean-Baptiste Huët