Bag Wigs and Bags in the 18th Century

One of the definitions Johnson provides for the word bag is “An ornamental purſe of ſilk tied to men’s hair.”

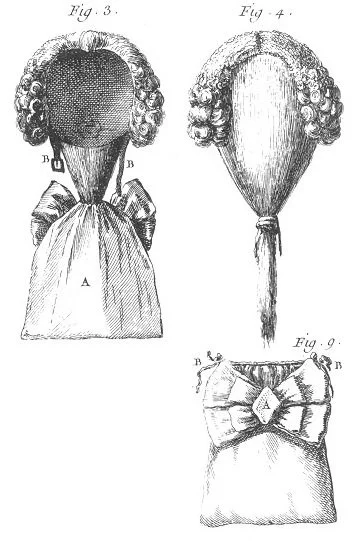

Bag wigs are illustrated in the Perruquier, barbier, baigneur-étuviste section of Diderot’s 1765 Encyclopédie (Planche VII, Fig. 3 & 4 “Intérieur & extérieur d’une perruque à bourse,” and Fig. 9, “Bourse. A, la rosette. B B, les cordons”), and in Garsault’s 1780 L’art du perruquier.

Plocacosmos (1782) provides brief instructions:

If the hair is worn in a bag behind, you muſt tie it in the ſmalleſt twiſt or club you can, to keep the bag on : the bag to be put on after powdering behind.

Bags and bag wigs are also referenced in newspaper advertisements and trade cards. They’re listed on the trade cards of George Laidler and depicted on the trade cards of Richard Arkwright, William Brasnell, William Johnson, and Jonathan Whitchurch.

Carl Julius Weber (Briefe eines in Deutschland reisden deutschen) points out that two-thirds of all the Haarbeutel in Germany could be found in Saxony.

Such bags occasionally appeared into the 19th century, surviving even longer in formal English court clothing (see notes with V&A T.61 to C, F to L-1918 and Manchester Art Gallery 1962.44/6) and also (maybe?) as costume pieces (like Bayerisches Nationalmuseum 96/440, Met 2009.300.2178, and V&A T.1018-1913).

Additional Resources

Tied Up: Neckwear in Reigning Men

Wigmaker's Shop Historical Report, Block 9 Building 29B: Wigmaking in Colonial America

Women Merchants and Milliners in Eighteenth Century Williamsburg

Personal Effects: Wigs and Possessive Individualism in the Long Eighteenth Century

Hair, wigs and wig wearing in eighteenth-century England

The Wigmaker in Eighteenth-Century Williamsburg

Fashion History Timeline, 1720-1729

Macaroni Men and Eighteenth-Century Fashion Culture: 'The Vulgar Tongue'

Hanging the Head: Portraiture and Social Formation in Eighteenth-Century England

Fig. 3. & 4. Intérieur & extérieur d'une perruque à bourse. A, la bourse. B B, les jarretieres.

9. Bourse. A, la rosette. B B, les cordons.

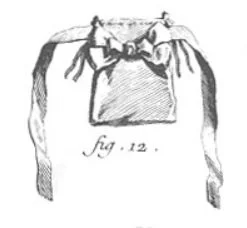

12. Bourse à cheveux.

© The Trustees of the British Museum. Shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence.

The bag wig as foppish French fashion

The Bag-Wig and the Tobacco-Pipe: A Fable (1752) encapsulates an English (and Anglo-American) attitude toward bag wigs:

A bag-wig of a jauntee air,

Trick’d up with all a barber’s care,

Loaded with powder and perfume,

Hung in a ſpend-thrift’s dreſſing room …

“ Why what’s the matter, goodman Swagger,

“ Though flanting, French, fantaſtic bragger,

“ Whoſe whole fine ſpeech is (with a pox)

“ Ridiculous and heterodox.

“ ’Twas better for the Engliſh nation

“ Before ſuch ſcoundrels came in faſhion;

“ When none ſought hair in realms unknown,

“ But ev’ry blockhead wore his own.

An essay published in 1732 in The London Magazine likewise complains about contemporary fops: “Our Anceſtors, great and glorious in the Field, gave Laws to all Europe; but our People of Faſhion are govern’d by every foreign Taylor and Millener. To be extremely fine now, is to be extremely ridiculous; ’tis to wear a French Bag-Wig and Clock-Stockings, or a Dutch Head with a plain Scarf.”

Also, from A Key to the Time (1735):

I ſhall ſpend the Winter where I am, but intend to pay my Reſpects to you next Summer in a Suit of Cloaths A-la-mode de Paris, and this brings me to ſay ſomething of the French Dreſs. The Mens Coats are cut pretty much like ours, but all the young Fellows, and ſome of the old ones, wear their Wigs in Bags and a Ribbon (inſtead of a Cravat) ty’d in a Knot under their Chin, which they call a Solitaire. Some of them this Summer have made their Appearance in white Bags and Roſe-coloured Solitaires, which to tell you the Truth, dear Ned, does in my poor Opinion look a little fantaſtical.

The bag wig appears in several satires of French fashions. Benjamin Franklin mentions bag wigs in a letter from Paris in 1767:

Perhaps I have suffered a greater Change too in my own Person than I could have done in Six Years at home. I had not been here Six Days before my Taylor and Peruquier had transform’d me into a Frenchman. Only think what a Figure I make in a little Bag Wig and naked Ears! They told me I was become 20 Years younger, and look’d very galante.

Portraits (and many of the extant examples) below indicate that bag wigs eventually became more widespread in 18th century England and Anglo-America.

Extant bags & bag wigs

National Museums Scotland A.1914.328 H, “Wig, with a black bag, decked with three rosettes to hold the queue, part of a gentleman's suit: English, Georgian Period, 1760”

London Museum A15092, c. 1766-1799; “Man's horsehair wig. The horsehair is mixed grey and white, reading as a warm grey from a distance. Five rows of curls extend back from the front forehead edge. Single curls run from temple to nape on either side. Straight ponytail gathered into a black silk queue bag with black silk ribbon bow. Horsehair woven at the base with two cotton threads, which are stitched down to the cotton base support. This support is stained and discoloured, possibly through original wear. The support is reinforced with cotton twill tape over the seams and at the edges. The two original plain weave cotton ties are fastened at each corner approximately at the earlobe. There are flat metal supports inside the lining near the ties which show where the fabric has worn through.”

Germanisches Nationalmuseum T2424, a black silk bag with silk ribbons and linen stiffening, c. 1770

Morristown National Historic Park MORR 3932, a gentleman’s queue bag in silk and linen

V&A T.10:1 to 3-2010, three-piece brown wool day suit, France, c. 1780; “its black satin wig bag is still attached to the back of the coat … Black silk satin wig bag, with a decorative rosette. The tail of the wearer's hair or wig would have been worn inserted into the drawstring opening at the top.”

Royal Ontario Museum 971.164.A, coat of man’s 2-piece formal court suit in ribbed silk trimmed with ermine, England, c. 1780; “The coat has an attached black satin wig-bag with large ribbon rosette to prevent pomade and powder from staining the silk.” See also Fashion was in the Wig-Bag, which mentions that “The bag is weighed with husks to keep it lfat and was probably stitched on at a later date, when the suit may have been used for fancy dress or as a theatre costume.”

Mint Museum 2005.6A-C, three-piece formal velvet suit with a wig-bag attached at the back neckline of the coat, c. 1780

Chertsey Museum M.1995.26, “small rectangular black silk wig bag with silk tape drawstring at top, large black rosette with flat bow in centre, outer edge trimmed with black pleated ribbon in three layers; c. 1780-90”

V&A T.47-2015, “A man's wig bag of black silk with pinked rosette and black linen drawstring,” made in England c. 1780-1800

Mount Vernon W-2976, a hair bag known to have been worn by George Washington, c. 1785-1800; “Black silk hair bag constructed of black silk taffeta lined with plain-weave linen buckram; the upper edge has been folded under twice with a .5" hem and stitched by hand with black silk thread in a running stitch; both of the upper side seams are open, 1.5" on the proper right and 3.75" on the proper left; the back of the bag is padded with soft material that extends 3.25" up from the lower edge; stitched to the front of the bag is a black grosgrain ribbon rosette which consists of six loops of black ribbon on top of which is sewn a rosette made from several lengths of ribbon, clipped on each end to form a sawtooth edge, stacked together and tied at center, and arranged to flare out in a circle.”

MFA 43.2563, a bag for a wig queue: “Ribbed, black silk rectangular bag with tie strings at the top. A large ribbon medallion and ribbon bows are attached. Contains horse hair.”

V&A T.27-1938: “Man's wig bag of black silk taffeta, lined with canvas. It is rectangular in shape, pleated at the top with a opening in the right side seam at the top. There is a bow-shaped trimming of black silk at the top edged and decorated with 3 types of black silk ribbon.” British, c. 1790-1810

Wig belonging to Henry Bromfield and replica; see also Head Over Heels

Met 2009.300.6199, wig bag, probably British, c. 1830-1840

George Washington’s accounts indicate that he had ordered “2 Wig, or Hair Bags” from England in 1760, and bought “a hair Bag” in 1771.

Portraits of Washington from the 1790s – including this portrait by Edward Savage – show that he was continuing to wear this style, quite some time after it had been fashionable. (The ribbons at the top of the bag are just visible behind his collar.)

Mount Vernon’s collections include one of these hair bags, and fragments of another.

Descriptions, portraits, and artwork depicting men wearing bag wigs

The Garter by Jean François de Troy, 1724

The Declaration of Love by Jean François de Troy, c. 1724

Mercure de France, May 1726: “Les Perruques le plus en vogue ſont noüés; on en porte beaucoup en bourſe; la friſure en eſt moutonnée, c’eſt à-dire, en petites boucles, qui forment comme deux oreilles d’Epagneuls & ces bourſes ſont ſort variées & differemment ornées. La queuë prend ſouvent la place de la bourſe, principalement chez les jeunes gens qui porrent leurs cheveux.”

Les Perruques à faces by Antoine Hérisset, 1729

The Declaration of Love by Jean-François de Troy, 1731

Philippe Coypel by Charles-Antoine Coypel, 1732

The Chorus of Singers (or Rehearsal of the Oratorio 'Judith') by William Hogarth, 1732

Rudolf Fisher Von Reichenbach by Johann Nikolaus Grooth, 1732

The Oyster Dinner by Jean-François de Troy, 1735

Frederick Louis, Prince of Wales by Philip Mercier, c. 1735-1736

The Hunting Meal by Jean-François de Troy, 1737

Head-dresses by Bernard Lens

Interior of a picture gallery with the collection of Cardinal Silvio Valenti Gonzaga by Giovanni Paolo Pannini, 1740

Unknown man in a blue suit with gold braid

The Game of the Cooking Pot by Pietro Longhi, c. 1744

Sir Lucius Christianus Lloyd by Allan Ramsay, 1745

Charles Frederick William, Prince of Leiningen, c. 1745-1755

Charles Willing by John Wollaston the younger, 1746

Industry and Idleness: The Industrious ’Prentice Lord-Mayor of London by William Hogarth, 1747

Isaac Winslow by Robert Feke, c. 1748

Edward Curtis of Mardyke House, Hotwells, Bristol by Marco Benefial, 1750

Two boys building a house of cards by Jean Anton de Peters, c. 1750

Self-portrait of Maurice Quentin de La Tour, c. 1750

Portrait of a man, 1750s

A prison scene, c. 1750-1753

Double portrait by Alexander Roslin, 1754

Back view of a well-dressed gentleman (or servant?) by George Keate, 1754

The Humours of an Election III: The Polling by William Hogarth, 1754-1755; at the far right of the panel, “staring at [the Whig candidate] is a red-coated caricaturist with a bag-wig who has produced an unflattering sketch of him to the great mirth of two rough looking men.”

Robert Wood by Allan Ramsay, 1755

Portrait of a man in a red suit, c. 1757-1761

George Lucy by Pompeo Batoni, 1758

Baron Thure Leonard Klinckowström by Alexander Roslin, 1758

The gentlemen of the duc d’Orléans in the uniform of Saint-Cloud by Carmontelle; also portraits of Monsieur Chalut de Verin, Charles-Louis de Beauchamp, comte de Merle, Carmontelle, lecteur du duc d’Orléans, Monsieur Duchemin, de Nemours, Monsieur de Feuillant, Monsieur Du Rouet, Monsieur Valentin, contrôleur de la bouche du duc d’Orléans, Monsieur Poisson, 1er valet de chambre de Monsieur le duc d’Orléans, a man, another man, Milord Farnham, Monsieur le prince de Gavre de Bruxelles, Monsieur le marquis de Sorba, envoyé de Gènes, La Beaumelle, Monsieur Duclos, secrétaire perpétuel de l'Académie française, etc.

Costume de Mr. Granger, c. 1760

Portrait of a young man by Pompeo Batoni, c. 1760-1765

John Talbot by Thomas Gainsborough, early 1760s

William Hanson by Thomas Gainsborough, c. 1761

Prince Vladimir Golitsyn Borisovtj by Alexander Roslin, 1762

James Bruce of Kinnaird by Pompeo Batoni, 1762

Charles Wyndham by William Hoare, 1762

William Leyborne Leyborne by Thomas Gainsborough, c. 1763

The English ambassador in The audience with the Grand Vizier by Francis Smith, c. 1763-1769

Henry Harrington, c. 1764

Boursier, Encyclopédie ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers, Paris, 1765 (plate 2, figure 12: “Bourse à cheveux.”)

Portrait of a gentleman in a fancy waistcoat, c. 1765

Count Kirill Grigorjewitsch Razumovsky by Pompeo Girolamo Batoni, 1766

Les hasards heureux de l’escarpolette (The Swing) by Jean-Honoré Fragonard, c. 1767-1768

Governor John Wentworth by John Singleton Copley, 1769

The Right Honble Norborne Berkeley, Baron de Bottetourt, late Governor of Virginia, 1774; a “1 New Silk Wig Bag” appears in his 1770 inventory

Charles-Michel-Ange Challe by Louis Rolland Trinquesse, c. 1770-1780

King Gustav III of Sweden and his brothers by Alexander Roslin, 1771

Le carquois epuise, c. 1775

George Herbert by Pompeo Batoni, 1776

James Whatman by John Smart, 1777

La Dame du Palais de la Reine, 1777

L'Accord parfait, 1777

George Stubbs, c. 1777-1779

Joseph Vernet by Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun, 1778

After the Opera by Jean-Michel Moreau le Jeune, 1778

A portrait of a gentleman, perhaps the architect Jacques Gondouin, c. 1779

L’art du perruquier, 1780: “La perruque en bourſe ſe fait le plus ſouvent à oreilles, rarement à monture pleine; alors le liſſe prend ſur l’oreille mème au-deſſous des corps de rangs.”

Self-portrait by Izaak Jansz. de Wit

Daniel Danvers by William Hoare, 1780

The Benevolent Physician, 1782

Jean-Baptiste Pigalle, 1782

John Adams by John Singleton Copley, 1783

Jacques-Antoine de Beaufort by Adélaïde Labille-Guillard, 1783

Prince Charles Edward Stuart, eldest son of Prince James Francis Edward Stuart by Hugh Douglas Hamilton, c. 1785

Silhouette portrait of a man by Joseph Adolph Schmetterling, 1785

William Cowper, in a 1785 letter (written when he was 54 years old), describes himself: “As for me, I am a very smart youth of my years; I am not indeed grown grey so much as I am grown bald. No matter: there was more hair in the world than ever had the honour to belong to me; accordingly having found just enough to curl a little at my ears, and to intermix with a little of my own that still hangs behind, I appear, if you see me in an afternoon, to have a very decent head-dress, not easily distinguished from my natural growth, which being worn with a small bag, and a black riband about my neck, continues to me the charms of my youth, even on the verge of age.”

Karl Friedrich Abel by John Nixon, 1787

Portrait of a man by Johannes Heinsius, 1787

Frederik Vilhelm Wedel-Jarlsberg

Jean-Baptiste Bréval, c. 1790

Portraits of George Washington by Adolf Ulrik Wertmüller (c. 1795), Edward Savage (c. 1796), Gilbert Stuart (1797), and Gilbert Stuart (1798).

References to Washington purchasing wig/hair bags in 1760 and 1771.

See also George Washington’s Oh-So-Mysterious Hair, Mount Vernon W-2976 (one of his hair bags), and Mount Vernon W-3294/A-C (“fragments, carefully preserved by relatives of Martha Washington, [which] may represent a piece of Washington's hair ribbon, linen lining from his hair bag, and a lock of his hair”)

Remains of good old fashions, exhibited in the Federal Court, Richmond by Benjamin Henry Latrobe, 1797

A wigmaker, c. 1818

Satires and caricatures

Taste in High Life by William Hogarth, 1742

Study for a satirical print on Orator Henley by Louis Philippe Boitard, 1746

The Laughing Audience by William Hogarth, 1761

A French valet de chambre in The Frenchman at Market, 1770

Que je suis enchanté de vous voir!, 1770

A Half Pay Officer Who Has Been at Dinner with Capn Broad, 1771

A French hairdresser in The Politician, 1771

A fox (Charles Fox) in The Young Heir among bad Councellors, or the Lion betray’d, 1771

Wilkes in The Double Discovery, 1771

A Macaroni Print Shop, 1772

Lady Fashion’s Secretary’s Office, or Peticoat Recommendations the Best, 1772

The Shuffling Macaroni, The Scavoir Vivre, The Bank Macaroni, and The Protecting Macaroni, 1772

Wigs, 1773

Piety in Pattens or Timbertoe on Tiptoe, 1773

Search the World you’ll ſeldom ſee ___ Handsomer Folks than We Three, 1775

Il Milanese, 1780

Caricature of a man in a bag wig, 1780

A Frenchman in Politeness, after 1780

Deep Ones, 1777

A New faſhion’d Head Dress for Young Miſses of Three ſcore and Ten, 1777

The barber riding to Margate, 1782

Razor’s Levée, or ye Heads of a New Wig Ad___n on a broad Bottom, 1783

An author in Bookseller and Author, 1784

Le Chicaneur, 1784

1784, or the fashions of the day

The Meeting of the Legion Club, 1787

Quartiers du fameux D’Alton / Exploits manqués, 1787

An actor in A Lyceum oddity or stop him who can!, 1788

A smart, 1790

The Itinerant Language Master, 1797

Lust tot onderzoek, c. 1800-1805

A Barbers Shop, 1811

Le Lever des Papas, 1815